Uncertainty, University and a Theatre Teacher

Chris Marshall takes on a familiar role at The Tampa Repertory Theatre

“So now here I am, walking through the [winter] twilight, to [the Studio 120 Theatre at USF], followed, presumably, by my [comedic friend]. What am I feeling? Fear, certainly- the touch of fear one always feels for a teacher, an employer, for a [director].” – Michael Frayn, Copenhagen

Yes, I used some of Michael Frayn’s words to explain myself as I approached the threshold of the theatre. Admittedly, I was terrified, much like Frayn’s character, Werner Heisenberg. I felt similarities between us as he approached the home of his old teacher, employer and partner, Niels Bohr in 1941. I was just like him, in a slightly more modern predicament, about to watch my theatre teacher act as a lead in a play unknown to me. Yes, you are correct. The characters in Copenhagen are the same people you have read about in your textbooks. And as portrayed in the play Copenhagen, Heisenberg and Bohr are so much more than “those dead science guys.”

Copenhagen, written by Michael Fray, is a play that premiered in 1998. It opened on Broadway in 2000 and a film interpretation was made in 2002. The play is based on a mysterious historical event in 1941 in Copenhagen, Denmark that concerns the aforementioned scientists. The play shifts between the characters’ time in the afterlife to the characters reliving their ambiguous past together.

I found myself chuckling at the name dropping that occurred throughout the production. Frayn certainly did his research while composing his play in order to paint a complete and detailed historical image for the audience. Or, perhaps, he was just trying to assess if we had all passed our high school physics classes or, at least, stayed awake. If you stayed awake, the names Schrodinger, Rozental, Moller and Einstein might have stood out to you. If you passed, you would have quickly made the connection between those names and Theoretical Physics.

A play about physics… and chemistry and history. A play about calculations and uncertainty that was stuffed with too many dates for Valentines Day to handle. It was chaotic while also being exceptionally elegant. In my time as an audience member, I might have learned more than I learned in a semester of rigorous schooling. Don’t test me on what I watched, though, because I’m not quite sure that the problem presented at the beginning of the play ever quite resolved itself. Which meant that there was no correct multiple choice answer. I noticed the discomfort on the faces of a few audience members as they struggled to comprehend. We live in a world that appreciates brief, correct answers. We appreciate predictability. But, as Copenhagen dares to say, we are subject to our own uncertainty principles, much like the electrons in Heisenberg’s experiments.

Even the set, designed similarly to the Flex at Berkeley, was a critical storytelling element. The theatre was a black box, so much of the world of the play had to be created with lighting and immersive storytelling. It was disorienting at first, like it is learning the rules to a game for the first time. However, after the intermission, I felt that I had a decent grasp of the rules in this production.

- All characters, Heisenberg, played by The Director of Berkeley’s Upper Division Theatre, Christopher Marshall, Bohr, played by Ned Averill-Snell and Margrethe, played by Ami Sallee, must remain on stage at all times.

- The lighting is the only way to distinguish the transition from the afterlife, to the past, back to the afterlife.

- The spotlight, a central beam that descends from the ceiling to the middle of the stage is to split, like you would imagine an atom to split, when the characters find themselves amidst heightened conflict.

- The chairs are almost exclusively to be moved by Margrethe.

I found the last rule particularly intriguing. As I carefully observed, I began to formulate a hypothesis about the chair adjustments. In the middle of the stage, there was a circular chalk design drawn on the floor. It extended outward in ribbons and loops and I immediately began to mentally refer to it as the “mandala.” The mandala was most certainly representative of an atom, or an explosion, and it was a fantastic visual tool used throughout the production. As characters searched for a definitive recollection of their motives during Heisenberg’s visit in 1941, the chairs shifted locations. The closer the characters seemed to be to an answer, the closer the chairs moved to the middle of the circle, or the nucleus of an atom, or the center of an explosion. When fighting broke out, the chairs moved away. It was like the push and pull of tides; the process repeated itself throughout the night. I took my hypothesis to the next level by predicting that the play would end with all three chairs in the middle with an indisputable solution agreed upon by the characters. My greatest disappointment was discovering that I had guessed incorrectly.

However, my greatest joy was watching my ATE teacher participating in a craft he cares so much for. Christopher Marshall acted with finely tuned technique and an energy that kept the stage jumping with life. Under the lights, under the pressure of his students coming to see him, he glowed. He was clearly well rehearsed, and it appeared as though the words he said were being spoken for the first time, like his tears were cried for the first time on that stage. Marshall was a believable Heisenberg, unsure of himself, desperate to understand how physics could possibly be applied to the human psyche. The other two actors were marvelous as well. Sallee was purposed and a light-hearted element in the production. Averill-Snell was everything you would expect to Niels Bohr to be, with an added, genuine sense of paternity. The fast-paced scenes never appeared to miss a beat and all characters moved with devised purpose. I loved the way they listened to one another, and I appreciate the fact that I considered my theatre teacher unrecognizable. He was Heisenberg, and now I’m uncertain if I will ever read a textbook the same way.

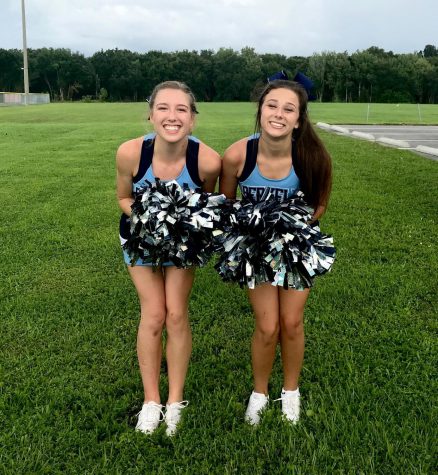

MARSHALL SPOTTED: Between Ami Sallee and Ned Averill-Snell stands Christopher Marshall, the Director or Berkeley’s Upper Division Theatre, portraying Werner Heisenberg in USF’s small, intimate theatre.

MY COMEDIC FRIEND AND HER PLAYBILL: Sofia Leche ’20 stands with me during intermission, an hour and a half after the play began. We discuss atomic bombs and chairs during the brief break.

ACTIVE LISTENING: Heisenberg and Bohr listen carefully to Margrethe as she explains to the two men what happened between them the night of Heisenberg’s visit in 1941.

Tess is a senior who has been writing for the Fanfare since her freshman year. She’s a dedicated journalist, a creative storyteller, and a positive teammate....